Helping health care providers have excellent person-centred conversations

Quick reference guide for different discussion types

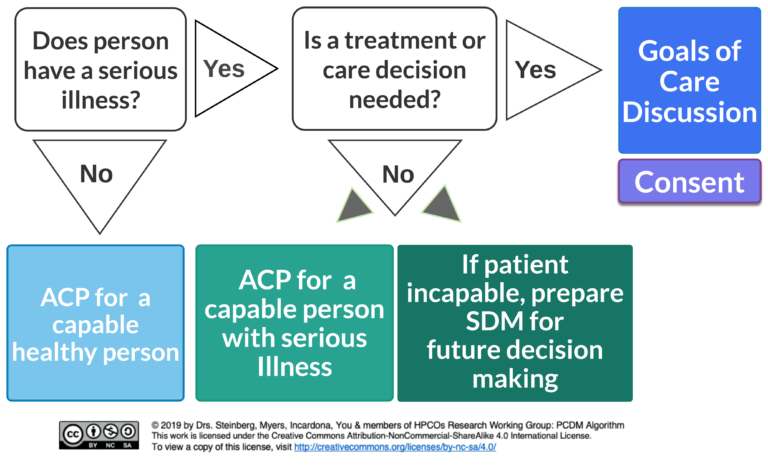

Determine person’s substitute decision-maker (SDM) for future decisions

Prepare the SDM for future decision-making by exploring a person’s overall values and priorities

Note that this does not create consent for future treatments

Ensure SDM is aware of patient’s values and goals and SDM responsibility

Anyone can do this – doesn’t need a healthcare practitioner

Primary care teams ideal as they have contact with healthy persons

Introduce ACP

Ask your patient if they know about ACP and are interested in learning about it. Provide resources to the patient and their SDM

Educate:

About ACP – that it is to confirm an SDM and prepare an SDM to make future decisions if needed

Choose an SDM

Help your patient confirm an SDM who will respect their values in the future in the event patient becomes incapable to make a decision.

Remember, your patients has an automatic SDM based on hierarchy – your patient may want to appoint someone else — and that requires a power of attorney (POA) document.

Prepare the SDM

Prepare the SDM by encouraging or facilitating a discussion between your patient and their SDM to ensure the SDM is aware of the person’s wishes, values & beliefs.

In the future, if your patient is too sick to consent, the treating physician MUST get consent from the SDM, not from another health care provider, nor from a document. There is no legal mechanism for written advance directives in Ontario. All consent must come from the SDM, so it is most important that the SDM know your patient’s values and have access to any documentation that is meant to give them material upon which to consider giving or withholding consent.

Conversations are about Values, Beliefs, Wishes and Goals

Remember, for healthy patients, discussion is hypothetical, as patient is healthy. Discussions focus on values, priorities, wishes and goals. Rarely it covers specific treatments a patient would or would not want, e.g. dialysis, feeding tubes and/or intubation.

Better is to explore value-based questions such as:

What makes my life meaningful? (e.g. time with family or friends, faith, work, hobbies)

What do I value most? Being able to (e.g. live independently, make my own decisions, recognize or talk with others)

What are the three most important things that I want my SDM, family, friends to understand about my future personal or health care wishes?

See HPCO Practical Guide to ACP for more information

Discuss who is person’s automatic SDM

Ensure SDM aware of role and aware of person’s values to use for future decisions

Use conversation guides/education modules focused on values rather than checklists.

Examples:

- ACP Conversation Guide

- Speak Up

- Respecting Choices*

- HPCO ACP modules

*with modification for Ontario contextMany resources to help you develop knowledge and skill

Anytime

Link to periodic visits such as preventive screening visits

Create flag in EMR

Who is patient’s automatic SDM?

Learn about potential future role

Understand person’s wishes, values & beliefs

Participate in ACP conversations

Same as for ACP with a healthy capable person

PLUS:

Explore and Educate

the person & SDMs about illness (expected course, where the person is at on the disease trajectory & management and likely decisions in the future)

the person’s & SDM’s information needs

the person’s goals and values to help prepare them and their SDM for future decision-making

All health care practitioners have a role in this conversation

- SDM confirmed

- SDM understands role

- Illness is understood

- Information needs are met

Goals & values explored between person & SDM

Same as for healthy person:

Introduce, assess readiness, identify an SDM.

BUT, additionally

Assess illness understanding

Provide education if necessary and patient ready

Use Conversation guides/education modules focused on values rather than checklists

Examples:

- ACP Conversation Guide

- Speak Up

- Respecting Choices*

- Serious Illness Conversation*

- HPCO modules

*with modification for Ontario context

Anytime a person is capable, and no treatment or care decision is being made

Use EMR to set reminders

Link to existing routine care:

- Periodic health exam

- Preventive health screening

- Routine disease monitoring visits

Following resolution of acute illness or change in health status

Learn about potential future role

Understand person’s wishes, values & beliefs as well as person’s illness

Participate in ACP conversations and attend healthcare visits at the patient’s discretion

Illness educator

Explore and Educate the SDMs about the person’s illness (expected course, where the person is at on the disease trajectory) & management

Educate about the role of the SDM in decision-making and consent

Explore SDMs information needs

Address limits of the role of this conversation given the uncertainty of future health care needs

- SDM confirmed

- SDM understands role

- SDM understands illness

SDM reflects on person’s prior capable wishes values, beliefs and how these will relate to decision-making (when it’s required)

Use skills learned from conversation guides/modules to:

- Educate the SDM on their role

- Focus on values and priorities

SDMs cannot express wishes on behalf of incapable persons

Any documentation must clearly indicate that these are reflections of SDMs and are neither consent nor the persons’ prior capable wishes.

Anytime a person lacks capacity, and no treatment or care decision is being made

Link to existing routine care:

- Routine disease monitoring visits

- Following resolution of acute illness or change in health status

- Periodic LTC health review

Learnabout their role

Reflect on a person’s wishes, values & beliefs and prepare to apply them when decisions need to be made

Coach, guide and facilitate a person and/or SDM through GOC Conversations to propose/offer treatments or care

Educate to prepare a person or SDMs for upcoming decisions

Ensure illness or event is understood

Inquire about previous discussions of values, beliefs and wishes

Provide information about current illness, (including trajectory and what to expect in the future) or decision and options (preparation for informed consent)

Explore and identify the person’s goals

Determine together the treatment and care that best fits with the person’s goals

- Decisions or care plans aim to align with person’s goals (e.g. dialysis, feeding tubes, transfer)

- If available treatments do not align with person’s goals, practice supportive counselling and non-abandonment

Use conversation guides/education modules to learn skills.

Click on http://www.goalsofcaremodule.com

for an example of an elearning module

Other Examples:

- Serious Illness Conversation*

*with modification for Ontario context

Anytime a treatment or care decision is to be made

May require a series of conversations

Each GOC conversation doesn’t necessarily lead to a treatment decision

Goals and priorities need to be re-assessed with changes in health status and/or each treatment

Incapable person: SDM takes active role in decision-making and consent

Capable person: SDM can support decision making but no specific role for decision or consent

Practitioner offering treatment obtains consent

Determine capacity of the person

Identify the correct SDM If person is NOT capable of providing consent

Provide translator if needed

Provide assistance if communication barriers exist (non-verbal, hearing impaired etc.)

- Person or SDM either provides or refuses consent to proposed treatment/care

Use Health Care Consent Act

Ensure information is provided at health literacy level of the patient

Discuss risks/benefits in relation to individual patient goals and priorities

Must be obtained before any treatment or care is initiated

Consent is required even if ACP or GOC conversations have not occurred

Provides (or refuses) consent on behalf of the incapable person

Become a medical expert for your patient

Whenever possible, contact your patient’s subspecialist for information such as disease trajectory, options for treatment, prognostic information, previous conversations about goals. In complex situations, it may be necessary to plan a meeting of the treating team.

Acknowledge your feelings:

Am I feeling rushed?

Am I anxious about the conversation? Do I feel there is a “right” outcomoe? E.g. have I been instructed to get a DNR?

What assumptions do I have about this patient?

These feelings may interfere with your ability to really listen –

Once you recognize your feelings, put them aside and really focus on learning about your patient – his hopes, worries, ideas and goals

Put your agenda on hold:

Even if you have an agenda for this conversation – put it aside initially – try and follow the patient. The reason is that patients will listtento your agenda if they feel you have listened to and respected theirs.

You will be much more helpful if you first understand what lies behind your patient’s questions, need and worries.

Setting:

Lastly, remember all the communication skills you’ve already been taught: sit down, make good eye contact, introduce yourself, and ask permission to have the conversation

Explore your patient’s understanding

This may take more than simply asking: “what do you understand”

It may take several open ended questions, clarifying questions and exploration.

You need to listen closely and be patient.

Most importantly, do not judge the answers – use “unconditional positive regard” to assume your patient has more understanding than you think and let them tell you

Learn some communication skills to encourage your patient to speak

Asking open ended and clarfying questions

Offering reflections

Silence

Principles:

Your patient should be talking more than you — and more than 50% of the time

Your questions and responses should follow your patient’s lead

Think of this as coaching and guiding, not telling your patient what is correct

Watch the following short video as the physician ask Mrs. West (a 60 yr old woman with metastatic breast cancer) about her illness understanding.

Ask if patient ready to hear information

This is especially important if the information is significantly different from their understanding

Skills when giving information

Speak slowly

Pause after every few sentences and check understanding

Pause after any emotionally laden information to allow for emotional reactions

Use plain english – avoid medical language

Learn a few different ways to explore this — it may be different for different patients

“Given what we have talked about, tell me what is important to you?”

“As you think about the future, is there anything you are worried or concerned about?”

“Has your mother ever talked about what would be important for her if she were ever critically ill? Some patients have already discussed that they would want to focus on comfort…others would be willing to undergo more intensive treatments if we thought they could return to their previous condition…”

Use your best medical judgement to recommend treatments that may meet your patient’s goals.

For example, if your patient’s goals are to live long enough for an event, you might recommend treatments aimed at prolonging their life or reversing an active medical issue. For example, giving blood transfusion, IV antibiotics, etc.

Start with asking permission to make a recommendation and then after the recommendation, check in…

Phrases:

“I have heard a lot about what is important to you…Would it be okay if I made a recommendation? Given what you’ve said is important to you, I’d recommend we continue with chemotherapy…”

“Given what you’ve said would be most important for you father, I’d recommend we focus on his comfort and avoid treatments that will prolong his life and not add comfort…How does that seem to you?”